Innovation is defined by Oxford English Dictionary as “make a change in something established“ or “introduction of something new”, such as a method, idea or device. A similar but a more sophisticated definition is presented by Abernathy and Clark (1985), who illustrate it as:

”an innovation is the initial market introduction of a new product or process whose design departs radically from past practice. It is derived from advances in science, and its introduction makes existing knowledge in that application obsolete. It creates new markets, supports freshly articulated user needs in the new functions it offers, and in practice demands new channels of distribution and aftermarket support. In its wake it leaves obsolete firms, practices, and factors of production, while creating a new industry”.

Thus, this view clearly focuses on entering new unexplored domains and markets.

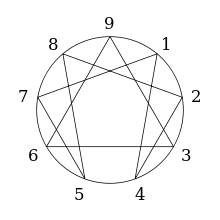

The Periodical system for Innovation

Keeley et al. (2013, here is the link to the book. I highly recommend if for anybody that is working with innovation) introduces an innovation framework, which is inspired by the periodical system from chemistry, that consists of three different main segments: configuration, offering, and experience. The first segment, the configuration aspect, focuses on the innermost workings of an enterprise and its business system. The second segment, the “offering category”, concerns with the core products and services of an enterprise, or a collection of these. Finally, the experience category focuses on the elements that the customers face in the regards to the enterprise and its business system.

All these three segments are also horizontally ordered as from left to right, according to its internal to its external impact and influences of the enterprise. In addition, the whole framework constitutes of further ten category types, which is grouped into the aforementioned three main segments (Figure 1).

The first type in the configuration segment is the “profit model”, which essentially involves how to convert “firm’s offerings and other sources of value into cash”. Hence fore, the focus in on having a deep understanding of what the customers cherish and aspire, in order to discover new revenue and pricing opportunities. It should be noted and clarified that a profit model differs significantly from a business model, mainly because a profit model only concerns with catching value and is not involved in the value creation process.

The second innovation type is “network”, which represents the opportunities that lies in both leveraging on one’s core competences and harnessing other firm’s strengths and assets to one’s advantage. This innovation type is thus closely associated with various co-creation and business ecology concepts, which will increase in an ever more connected global environment.

The third innovation type is “structure”, which focuses on how the company’s assets are organised in order to generate value. In other words, these innovations encompass the alignment and nature of company capabilities and assets, so that the configuration and management of these are structured and leveraged in the best possible manner.

The process unit refers to the primary activities and operations that are associated with producing the offerings of a company. Innovating in this division requires fundamental changes from “business as usual”, although the outcome, that is the offering, remains the same and unchanged.

The first innovation type in the offering segment is “product performance” which addresses the “value, features and quality of a company’s offering”. Often the traditional understanding of innovation is associated with this type, a goods-dominant logic perspective on innovation. The thumb of rule states that these innovations most often are easily copied by industry competitors, or reverse engineered, and therefore provide with only a temporary advantage.

The “product system” division refers to the bundling and connecting effects between products and services. The foundation for fostering these effects lies in interoperability, modularity and integration between otherwise distinct and separate offerings. Therefore, product systems are the blueprints for building valuable and protected and differentiated product offering entities, that strives for establishing ecosystem-like synergies within the company’s reach and boundary.

The first innovation type in the experience category is “service”. This division refers to the innovations that “ensure and enhance the utility, performance, and apparent value of an offering”. Thus, services function as a supporting element that improves the customer journey and reveals new overlooked value capabilities for the users.

The channel division involves all the conceptual innovations associated with connecting the value offerings with the customers and users of a company. In short, channel innovations are various new infrastructure solution concepts that conveys the final products or services to the end users.

The “brand” innovations helps the customers to remember, recognize and prefer the offerings of a company over other similar substitutes. The goal is to seduce and attract the customer with a conveyed promise that will make the offerings distinctive and unique. By doing this the offerings gain an immaterial advantage over its competitors that gives rise to new exploitable value dimensions.

The “customer engagement” is the final innovation type, and strives for designing and implementing a deep relationship between the enterprise and its users that symbolises meaningfulness and endeavours aspirations beyond the original commercial incitements. This means that the paradigm encompasses and stimulates an emotional dimension to the offerings of a firm, which give rise to a symbiosis effect between the company and its users.

Periodical tables might change…

It is clear that the 10 types of innovation is a pragmatic model for classifying different innovations. However, innovations are obviously not as straightforward as the model suggests. The chategories may develop over time or new ones might be introduced etc., just like new elements are found and added into the periodical table, when new scientific breakthroughs are made . But the great value in this model is that it will help you seeing things from a different perspective. That in itself is a innovation!

/Drill

Information is increasingly being perceived as a valuable asset in today’s modern society, de facto that in some occurrences information is by far the most valuable asset of a business and its activities. This tendency is refered often with the quote: “data is the new oil”.

Information is increasingly being perceived as a valuable asset in today’s modern society, de facto that in some occurrences information is by far the most valuable asset of a business and its activities. This tendency is refered often with the quote: “data is the new oil”.