In everything you do, you need to have a clear understanding of “why” you are doing the things you do. In other words, have a plan. Not having one is planning to fail. Period. Having a plan is the same as having a clear vision and a mission.

By the way what is the difference between vision and mission? A vision is the ideal state you want to be in the long future, a roadmap of sorts. On the contrary, the mission is far more shortsighted and defines clear objectives, when the operating context and environment is taken into account. Still confusing, eh? What helps me to distinguish these concepts from each other is to compared them with the concepts of tactics and strategy in the following manner:

Tactics is winning a battle, while strategy is winning the war

Knowing this, so what is a business model then?

Orgins of Business model

The term “business model” was first time used in academic literature in 1957, but has since early 2000s gained more attention because of the emerging digital economy and therefore is a relatively young phenomenon and concept (Osterwalder, Pigneur, & Tucci, 2005). According to Fielt (2013) the concept is criticized often for being vague, fuzzy and not clearly defined. Also Slavik, and Bednar (2014) agree with this view, but establish that the different definitions can be separated into two categories: a purely economic view and an extended view, where the creation of value is considered. A purely economic business model definition is presented by Chesbrough (2006a) as “a useful framework to link ideas and technologies to economic outcomes “. By comparison, Osterwalder’s and Pigneur’s (2010) definition of a business model takes the value creation and capturing approach, which is illustrated as:

“the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value”.

In any case, it is clear that a general definition of business model is still out of sight within the academic context, though it seems that the focus is shifting towards the value generating and capturing perspective (Fleit, 2013). Therefore, the most complete conceptual definition so far is presented by Fleit (2013), who share similar elements with Osterwalder and Pineur, where a business model:

“describes the value logic of an organization in terms of how it creates and captures customer value”.

The best tool for visualizing the business model is the business model canvas, which I will explain in the next section.

The Business Model Canvas

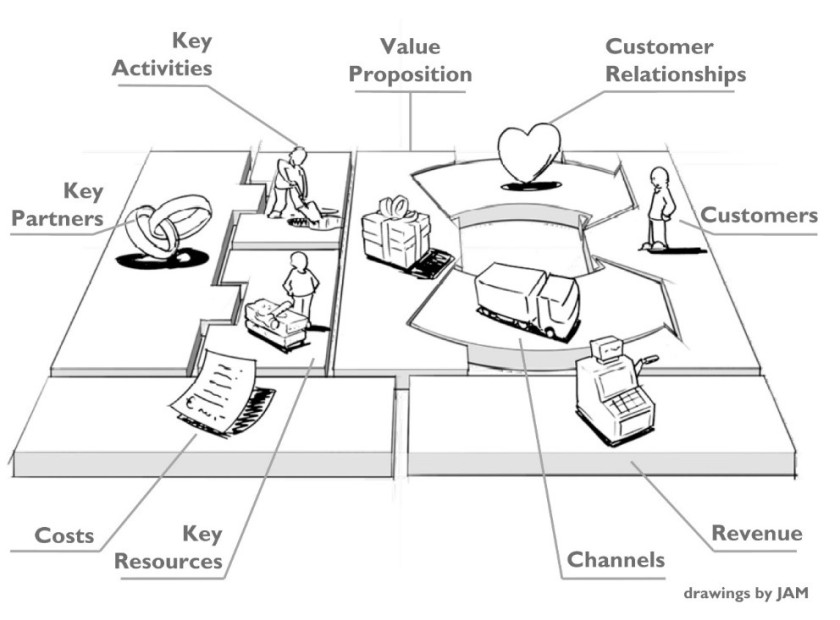

The business model canvas is a visual strategic management tool initially proposed by Alexander Osterwalder in late 2000s. According to Osterwalder (2012) the business model canvas framework is capable of both discovering all new business models and designing and describing existing ones. The model itself constitutes of nine fundamental building blocks, which are: customer segments, value proposition, channels, customer relationships, revenue streams, key resources, key activities, key partnerships and cost structure. In Osterwalder’s reference model (2012) the nine blocks or modules are placed in a prestructured order which in turn forms a rectangular entity or image (Figure 1) that is the final canvas.

The first block, customer segments, can be found in the upper right corner of the canvas (Figure 1). This conceptual block aims to identify the different groups of people and organisations that the enterprise wants to reach and serve. The customer segments are separated into groups based on: their specific needs; relationship requirements; profitability, their willingness to pay for different aspects of the offering; and how the distribution reaches them (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). Examples of different customer segments are mass market and niche market.

Figure 1. The business model canvas with its different modules (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010).

The second block, value proposition, is found at the heart of the business model canvas. This module involves a mix of various different elements catering to the customer segment’s needs (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) also recognizes elements and features that contribute to value creation which are newness, price, performance, customisation, design, brand/status, cost reduction, risk reduction, “getting the job done”, accessibility, and convenience/usability. All these elements are self-explanatory, except for “getting things done” which refers to the service aspect of helping the customer to achieve her desired results. For example, Rolls-Royce and GE sell operative hours of their machinery instead of the actual product (Wharton, 2007). Finally, all of these value generating elements can be divided into two major categories: qualitative and quantitative values (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010).

The third module, channels, is found in the middle-right part of the canvas (Figure 1). Channels are defined as the touch points of the customer, thus it plays a very central and important role regarding the customer experience. In addition, Ostwalder and Pigneur (2010) argues that channels serve important and crucial functions, such as: raising awareness of a company’s products and services; helping customers to evaluate the value proposition; take part in the actual delivering of the value proposition; and providing post-purchase support. Thus the channel process can be divided into five chronological phases, which are called awareness, evaluation, purchase, delivery and after sales (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010).

Customer relationship module, the block located above the channels block in Figure 1, portrays the type of relationship a company endeavour to establish with its customer segment (Osterwalder, 2012). Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) further elaborates this concept by presenting various categories in regards of customer relationships. The first is personal assistance, which encompasses real human interaction and cooperation. This relationship can further be refined into a separated category called “dedicated personal assistance”, which represents the deepest and most intimate possible relationship. Obviously, these kind of relationships takes a lot of time and effort to develop and realise. The third category is self-service, where the customer helps themselves and has no direct relationship with the company. Self-service can further be evolved into “automated services”, the fourth category, that is a more advanced concept, where sophisticated automation is embedded into the self-service processes. The fifth category is the utilisation and involvement of user communities. The rationale is that communities can exchange valuable knowledge and experience with a company’s customers. However, generally this concept face issues related to establishing this crowd sourcing platform with enough contributing parties and customers, who form these valuable network effects (Kemper, 2010). The last category is co-creation, which is a relationship where customers and vendor co-create value together, such as using influences from both parties to make the final product. It can thus finally be concluded that the motivation for all customer relationships are either customer acquisition, customer retention and boosting sales (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010).

The importance of Revenue Streams, the block in the lower right corner (Figure 1), is well expressed and formulated by Ostwalder’s and Pigneur’s (2010) citation: “if customers comprise the heart of the business model, Revenue Streams are its arteries”. Revenue streams thus refers to the money that the company generates through its activities and operations. Revenues Streams can further be divided into two groups: transaction revenues from one-time customers and recurring revenues that result from on-going payments (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). Revenue streams are obtained through several ways, such as asset sale, usage fee, licensing, lending/renting/leasing, subscription fees, advertising and brokerage fees.

The sixth block, key resources, can be found in the middle of the left half of the business canvas (figure 1). Key resources constitute of the most important assets of company and forms the core for a successful working business model (Osterwalder, 2012). Key resources can be divided into the following unique categories of physical, financial, intellectual and human assets.

The seventh, key activities, block is located on the left side of the value proposition block (Figure 1) and represents all the most important and crucial operations that a company carries out in order to make its business model work. Key activities can be organised in three categories: production, problem solving and platform/network (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). The production term consists of elements related to designing, producing, and delivering a product or good of a superior quality, therefore this group is often represented by manufacturing companies. The problem solving category differs in the sense that it tries to solve the problems of a customer and is often executed and realised by various different service concepts, thus this group is dominated by service specialised organisations. The last group, platform/network, concerns with matchmaking, networking, and software activities. Additionally, it must be mentioned that even some brands, such as Loui Vuitton, can also function as a platform, which expands the concept remarkably (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010).

In the upper left corner (Figure 1) one can find the eight block, key partnerships. Partnerships are a necessity in the modern business environment, where the focus on one’s core competencies and the ability to leverage these are often the deciding factor for a firm’s survival and profitability. Therefore, partnerships are sometimes the cornerstone of many business models (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). The motivation for seeking a partnership can be elaborated into three alternative synergy endeavours, which are optimization and economy of scale; reduction of risk and uncertainties and acquisition of a particular resource and activity (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). Ostwalder and Pigneur (2010) also suggest that partnerships can be distinguished into four differ types, which are strategic alliances between non-competitors, coopetition, joint ventures and buyer-supplier relationships. Where coopetition means that a strategic alliance between competitors are being formed, for example LinkedIn works intimately with competing headhunters (Cabrera, 2014). While Joint venture is per definition a business agreement, for a finite time, between parties to develop a new entity and new assets by contributing equity. The most famous joint venture setup was between Nokia and Siemens, who formed Nokia Networks (Ernst & Kim, 2002).

The last block, cost structure, is found in the lower left corner of the canvas (Figure 1) and illustrates all costs that arise from implementing the business model (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). There are two board extreme classes of cost structure, which are cost-driven and value driven. Most businesses apply a hybrid version of these two classes. Regardless of classification, the cost structure has four characteristics: fixed cost, variable costs, economies of scope and economies of scale (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). Where the “economies of scope” is the cost advantage that arises from producing many distinct goods, while “economies of scale” is the cost advantage arising from an enterprises size, output or scale of operations (Gilligan, Smirlock, & Marshall, 1984).

Final Evaluation of the Framework

The final business model canvas framework is a powerful tool for understanding and implementing business model innovation (Osterwalder & Pigneur, 2010). The real strength of the framework lies in its simplicity, practice orientation and its principle of “Plug- and Play” i.e. ability to start over with the remodelling process (Hong & Fauvel, 2013). However, the greatest short coming of the canvas framework is that it does not take into account the competition of the investigated object (Hong & Fauvel, 2013).

Finally, the importance of the business model is very well expressed by Chesbrough (2010), who illustrates that “the same idea or technology taken to market through two different business models will yield two different economic outcomes”. Therefore, a well-designed business model architecture is a necessity for running a business like a well-oiled machine.

In my opinion, a business model is thus a map for achieving the vision, but the map itself is stuctured based on the mission. Summa summarum, the business model is a concrete and detailed illustration of how to implement you mission (and the vision in the long term).

/Drill

References:

Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers. Long Range Planning, 43(2-3), 354-363.

Chesbrough, H.W., 2006a. Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business Press.

Ernst, D. and Kim, L., 2002. Global production networks, knowledge diffusion, and local capability formation. Research policy, 31(8), pp.1417-1429.

Fielt, E., 2013. Conceptualising business models: Definitions, frameworks and classifications. Journal of Business Models, 1(1), pp. 85-105

Osterwalder, A., 2012. Alexander Osterwalder: The Business Model Canvas. [Online Video]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2FumwkBMhLo.

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y., 2010. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers, Wiley, Hoboken, US.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. and Tucci, C.L., 2005. Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept. Communications of the association for Information Systems, 16(1), p.1.