The term “open innovation” was first introduced in 2003 by Henry Chesbrough, who suggested a new model and outline for obtaining innovations within the industrial context (Chesbrough, 2012). The background for the concept is that vertical models for developing innovations, such as R&D departments, are simply not sufficient enough in this modern hectic business environment. Therefore, ideas and knowledge needs to “open up” in a more freely and available manner. Open innovation as a concept has multiple interpretations and definitions, just as eskimos has many different word for snow, though the most fitting definition is proposed by Chesbrough (2006) hiself “the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation and expand the markets for external use of innovation”. Chesbrough (2012) further elaborates the concept and introduces two variants of open innovation: outside-in and inside-out.

Open innovation is “the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation and expand the markets for external use of innovation”

–Chesbrough

Inside-out

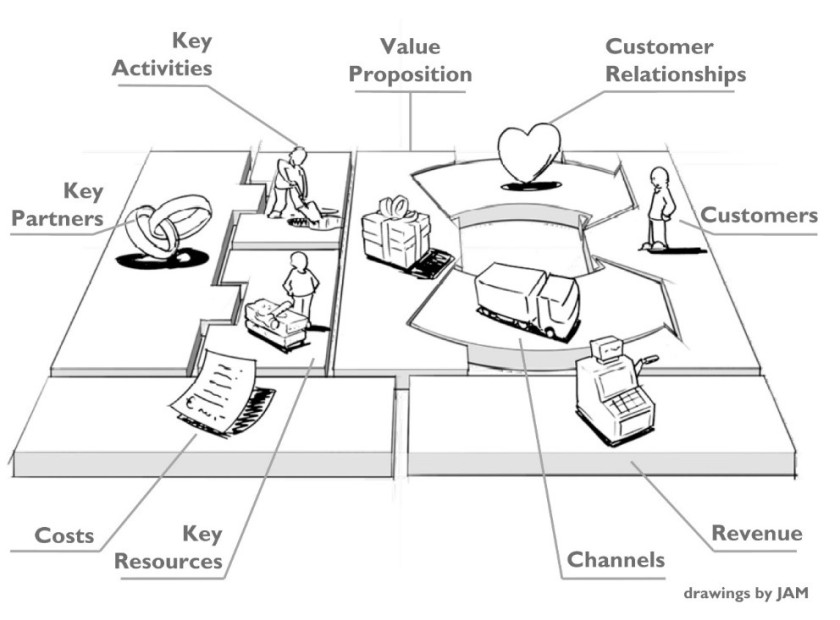

The inside-out open innovation perspective refers to the organisational outflow of unused or underutilized knowledge and innovations. In practice this concept suggest that internal developed knowledge and innovations could be used by other businesses in their business models and activities. This unorthodox flow of free intellectual assets is difficult to both comprehend and implement in practice, therefore this is clearly the vaguer and the least explored form of the two open innovation domains (Chesbrough, 2012).

Outside-in

The outside-in perspective has gained most attention within the academia and in practical applications (Chesbrough, 2012). The basic principle of the concept is that innovation ought to be assimilated and obtained to a company beyond the traditional organisational structure, meaning that the innovation processes are exposes to both external inputs and contributions (Chesbrough, 2012). Thus the outside-in perspective is a horizontal approach, where the innovations potentially emerge or get influences beyond organisations boundaries.

Analysis of old school R&D and Innovation

In the global economy there is an evident trend that points out that industry actors are increasingly consolidating through mergers & acquisition. According to Institute of Mergers, acquisitions and Alliances (2016) the value of M&As has since 2007 been around $4,5 trillion on a yearly basis, two folding the corresponding value observed in the mid-90s, likewise the number of M&A’s has doubled during that same time. Obviously this is partly as a result of a more globalised world, because cross boarder deals have increased from a sixth to 43 percent in 2014 during the same previous time period (Economist, 2014). However, despite the many different reasons and motives behind M&As, the World Economic Forum (2015) argues that this phenomenon is partially a means to an end for companies to outsource ideas and innovations. The argument is that the internal R&D activities are increasingly getting more expensive and that firms simply does not internally have the vast required know-how and resources anymore. Therefore, by buying start-ups, big firms acquire this R&D and talent that they lack. For example, this is one of the main reason why Google acquired Nest in 2014 for $3.2 billion. Hence, the statement proposed by World Economic Forum, that companies are outsourcing innovation and creativity, is fully valid one.

“M&As are a means to an end for companies to outsource ideas and innovations”

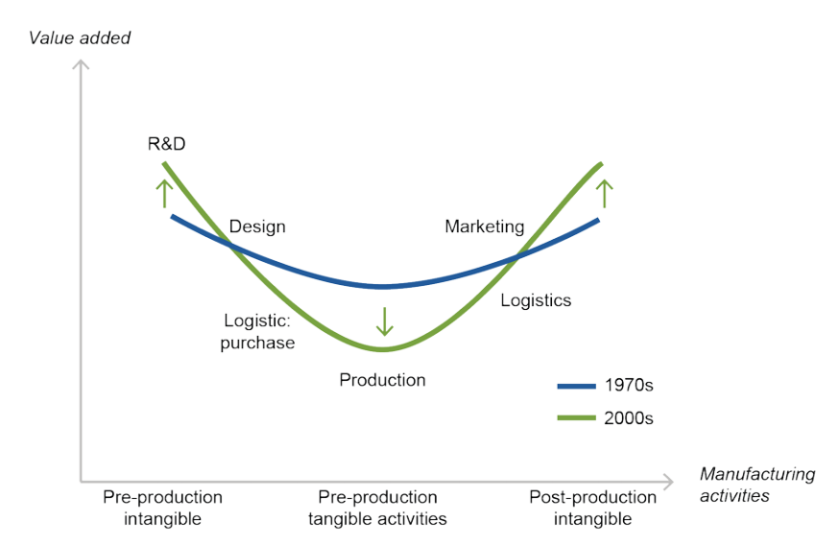

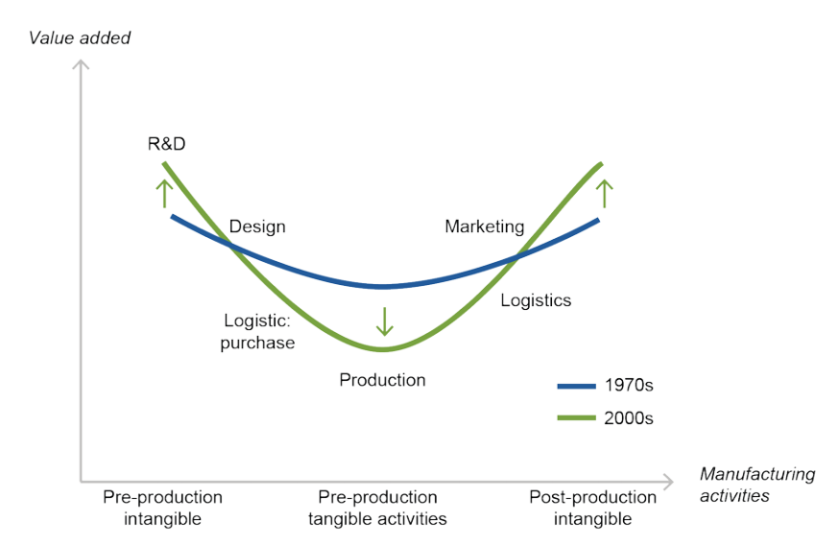

Meanwhile, it can be observed that R&D activities are perceived more valuable than ever in a value chain context. This appears clearly in the Figure 1, which illustrates the “smile curve”, where the value added properties in respect to R&D have clearly increased since the 70s. What is also noteworthy is that activities in the very end of the value chain is correspondently seeing the same development, while the production phase is plummeting in the in the respect to generated value. Naturally, this means that the focus of the value chain is shifting significantly towards the beginning and end of the value chain, thus supporting the previous stated argument.

Figure 1. Comparison between the “smile curves” from the 70s and 00s, which are illustrating the value added activities from a value chain perspective (Productivity Commission, 2016).

The importance and value deriving from R&D activities is further emphasized by the fact that product life cycles are constantly getting shorter. Generally speaking, this means that companies must produce more new offerings at an accelerated pace, while enjoying less revenues. Meanwhile, according to Eurostat (2016) the gross domestic expenditure on R&D (GERD) stood at €272 billion in the EU-28 in 2013, which is 43.8 percent higher than 10 years earlier in 2003. In essential this means that the expenditures are growing and corporations must come up with new more cost efficient and faster methods and structures for performing or obtaining R&D, because the traditional and conservative methods are not sufficient enough.

“Within the last 10 years the R&D expenditure has almost doubbled. This is unsustainable in the long run”

An example of this is the semiconductor manufacturer ASML who spent on average 78,000 EUR per employee on its R&D expenses in 2009, which was more than what most pharmaceutical and automotive firms correspondingly spent on R&D (Chick et al., 2014). However, the demand required an even more accelerated development pace, and from ASML financial perspective this was extremely unsustainable with its current investment model. The solution to this problem was unorthodoxly solved with a Co-Investment programme. Where ASML’s three largest customers – TSMC, Samsung and Intel – each contributed with financial resources of a total €1.38 billion over the next five years, for developing the next generation of lithography technologies (Chick et al., 2014). By doing this kind of network innovation, ASML was able to increase its development capabilities and meet the market demand. However, it can be argued that this composition structure is very similar to the open innovation paradigm because financials, instead of information, are “openly” shared among competitors for the common greater good of their industry.

Another yet similar example of open innovation paradigm, where the financials are shared instead of knowledge, is GE’s cooperation project with four venture capital firms in 2010. Together these parties arranged a challenge and pledged $200 million in funds to be invested in the best venture proposals related to renewable energy technologies (Chesbrough, 2012). The challenge received over 3800 venture proposals submission of whom 23 project was invested in. The overwhelming success of this challenge led to application of a similar model within the healthcare space a year later (Chesbrough, 2012)

Besides “openly” sharing pooled financial resources for acquiring financing and outsourcing of innovation projects, there have emerged other solutions on a smaller scale that are perhaps more aligned with the open innovation paradigm. Often these solutions are focused on crowdsourcing, i.e. seeking innovations and ideas from the crowd. For instance, Cisco has since 2007 arranged crowdsourcing challenges, called “I-Prize“, which targets and persuades young innovators to submit and present their ideas. The best winner is offered a financial reward of $250,000 in exchange for intellectual property rights for their idea (Cisco, 2016).

Procter & Gamble embraces a similar crowdsourcing strategy with their “Connect + Development” platform. The vision for this platform initiative was to increase the external ideas used in R&D from 15 percent to 50 percent (Gassmann et al., 2014). The final outcome of the initiative was that it managed to connect the firm’s 9000 researchers with over 1.5 million scientists around the globe. As a result, an enormous external ideation network was formed, that boosted the Procter & Gamble R&D productivity by 60 percent over five years after its release (Chesbrough, 2012; Gassmann et al., 2014).

The pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly takes this crowdsourcing strategy a step further by creating a transaction platform – “Innocentive“– that connects a wide range of high-technological solution seekers with solution proposals from 375,000 top experts in their field (Innocentive, 2016). The best proposal receives a financial award, while the platform receives its revenues from posting the solution seeker’s challenge and from acquiring the intellectual property rights for the winning idea (Innocentive, 2016).

The Buzz Phenomenon of Hackathons

Another more tangible implementation of open innovation is the use of hackathons. The term originates from the software industry and is a combination of both “hack” and “marathon”, which “implies an intense, uninterrupted, period of programming” (Komssi, 2015). The objective of a hackathon is to build a prototype in a relatively short amount of time, often about three days (Riikkala, 2016). Despite the short time frame, the results are astounding. For example, Juha Pankakoski, the CDO of Konecranes, expressed his overwhelming awe with the words: “it is scary how much can be achieved in such a short amount of time”, while Facebook, who is notorious for its hackathons, created the “like-button” during such a hackathon (Briscoe, 2014; Riikkala, 2016).

“Combine marthons with hack and Hackathons are formed”

Despite the impressive “shock therapy” that these hackathons have, the fact is that observations show that the effects are only temporal and will run off if exercised too often (Komssi et. al., 2015). Therefore, new long term aspects need to be distinguished and emphasised. One of these are that hackathons are an excellent opportunity for companies to acquire new talent and employees. For instance, Both Helvar and F-secure have hired new employees based on their accomplishments and performance in a hackathon that they respectively arranged (Kallonen, 2016; Komssi et. al., 2015). Therefore, it is conceivable to expect that hackathons will partly take over some of the human resource tasks or that human resource will take full responsibility for arranging these hackathons. Riikkala (2016), co-founder of Industryhack, is also playing with this idea of making hackathons into a company platform for acquiring new talent. For the time being, hackathons have proven to be an interesting concept of testing and harnessing external input, or outside-in knowledge, on a small scale.

We are open, but not to others!

A study conducted by Chesbroug and Brunswicker (2014) shows that 78 percent of large firms report that they exercise open innovation concepts, however, the main complication with the open innovation concept is that it is most often one-sided. This means that companies only focuses on the principle of outside-in flow of knowledge, while the inside-out perspective is considered as redundant; illogical; and even perceived as a threat. This despite the fact that many company patents and innovations never see the day light. For instance, P&G uses less than 10 percent of all their patents (Chesbrough, 2012). Likewise, other conducted studies show this pattern and estimates that about 70-90 percent of all patents are not used (Chesbrough, 2012). One explanation for this occurrence is that these innovations are simply not aligned with the company’s strategy or core competencies. But if this holds true, why cannot a third party harness this knowledge instead of being unused? Xerox for instance, challenged this norm and decided to encourage their employees of 35 different project, that didn’t get internal funding anymore, to take the ideas to the external market (Chesbrough, 2012). As it turned out most of these the projects failed, but a few succeeded and even became publicly traded companies. However, the astounding part is that the combined market value of these spin-offs now exceed that of Xerox (Chesbrough, 2012).

” 70-90 percent of all patents are never used”

Thus, it is clear that there is a lot of unused valuable knowledge and innovations, within companies, that aren’t being leveraged at all. However, the protectionism of companies makes sense, because why would companies share their heavily invested knowledge and resources for other to use, if there is no clear business logic involved? P&G have solved this problem by licensing innovations that go external, although this solution often only gives revenues on a rather minuscule level (Chesbrough, 2012). Hence, it is understandable that companies aren’t keen on releasing their ideas, because the risk-return relationship may not seem favourable when comparing the R&D sunk costs involved.

Patent lawyer Wert (2016) is of a different opinion and believes that patents are often misunderstood and should instead be perceived as business tool and a mean for stimulating innovation. This aims towards the tendencies that patents are to be used in negotiations and that competition drives to find new solutions to the same issue. Wert (2016) further states that patens instead play a central role of the “risk assessment” processes of a firm. This essentially refers to the idea that some patents should be considered a violation, but only if the risks involved are first evaluated and analysed. For example, when Google was developing their android operative system, parts of the Java API code were copied and consciously used without Oracle’s consent. However, the actual source code is not considered as an intellectual property, although the involving pseudo code is, thus, Google deleted the involving pseudo code – a strong argument for why Google was not facing criminal charges in the court (Wert, 2016). Therefore, Google’s conscious risk assessment and risk-taking were factors for their fortunate outcome and success. However, the other side of the coin is that firm’s have to, correspondingly, poses patent portfolios in order to have the upper hand in these negotiations or issues. Therefore, unused patents may serve a hidden purpose, or value, that is not taken into account.

Universities are Open Innovation Platforms

Clearly a successful open innovation strategy is all about implementation and aligned motives. For instance, from a theoretical viewpoint it could be argued that universities are originally designed to be ideal open innovation platforms. This is because at universities both inflow and outflow of knowledge take place on a large-scale, e.g. the education of students; inflow of external data sets and the release of scientific publications etc. Yet somehow this idealisation is not always aligned with the observed reality. It is well known that universities develop both advanced knowledge and make scientific breakthroughs on a constant basis, but the issue and problem remains in how to infuse this generated knowledge beyond the university boundaries. Therefore, universities become isolated and unleveraged R&D and knowledge entities, very similar to unused patents and innovations observed within companies.

“Universities are at times unleveraged open innovation platforms, very similar to the unused patents within companies”

According to Bergmark (2015), CEO at “Manufacturing Guide“, this trend was one of the main reasons for the starting the “Manufacturing Guide” initiative, which essentially is a “knowledge platform” whose mission is to mediate university knowledge with the manufacturing industry. A similar agenda and initiative is presented the biomedical research platform “eagle-i“, which is a “discovery tool built to facilitate translational science research” (eagle-i, 2016). The fundamental idea is to share scientific resources that else would appear “invisible beyond the laboratories or universities where they were developed” (eagle-i, 2016). Also the Finnish “PoDoCo” programme strives for integrating and reconciling young academic doctors and researches with the industry programme that last one or two years (Baiyere, 2016; PoDoCo, 2016). The programme itself is a collaboration initiative between universities, industries and foundations; whom together finance the salary expense (Baiyere, 2016). Therefore, there are many different initiatives that are encompassing to improve the open innovation tendencies of universities.

Are universities then harnessed and exploited by big players? According to Kalliokoski (2016) many of Technical Research Centre of Finland (VTT) projects have mainly receiving finance from large international multi-billion dollar companies, instead of national and local companies. This statement suggests that large corporations receive high quality R&D relatively cost efficiently through universities, and this of course happens often without sharing any mutual knowledge with the universities. Another example of this is the Brazilian cosmetic manufacturer Natura, who has an internal R&D team of about 250 employees, a pretty modest number for a company with 3.4-billion-dollars in sales, however, Natura makes up for this shortage by leveraging its sophisticated university network, which constitutes of 25 different universities worldwide (Keeley et al., 2013). Therefore, it could be argued that the knowledge flow between universities and large corporations is one-sided and that they, the large firms, exploit unleveraged government and publicly financed R&D sources and infrastructure to their advantage.

“Large firms exploit one-sidedly (outside-in open innovation) govenrment financed R&D sources and infrastructure to their advantage”

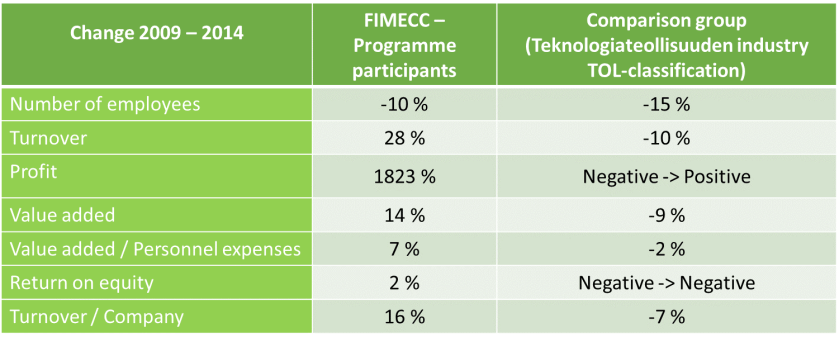

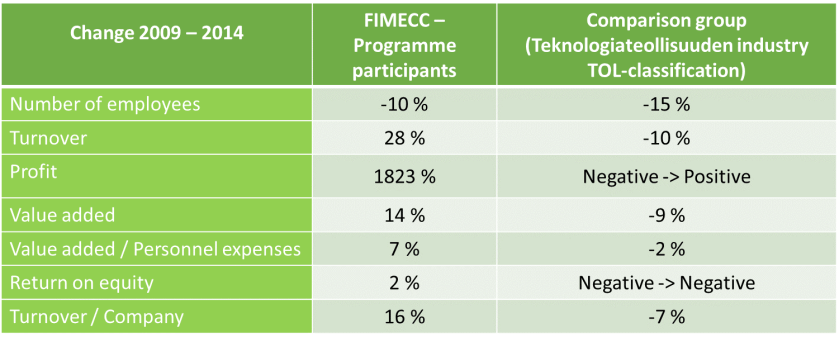

Irrespective of standpoint, it is clear that universities will play an important and central role for companies, who realise that their internal research is not sufficient enough and are looking for new R&D practices and possibilities. Especially in an open innovation context, universities show promising and convincing results. This appears clearly from results in Table 1, which is generated by company called “fimecc” (nowadays renamed “Dimecc“). In short, Dimecc is a Finnish company focusing on co-creation and cooperation between companies and universities, thus, creating and coordinating a true open innovation platform, where the different parties can together develop new innovations and ideas (Kulmala, 2016). The result form Table 1 clearly indicates that fimecc has had a significant impact on the companies involved, when compared to other companies who have not taken part in the programme. Of course some of the numbers are a bit misleading. For eample, 1823% increase in profits over a time period after 2008, mankind’s worst economic depression. Despite this distortion, the facts evidently point out that the programme participants are outperforming in every single category.

The True Power of Open Innovation

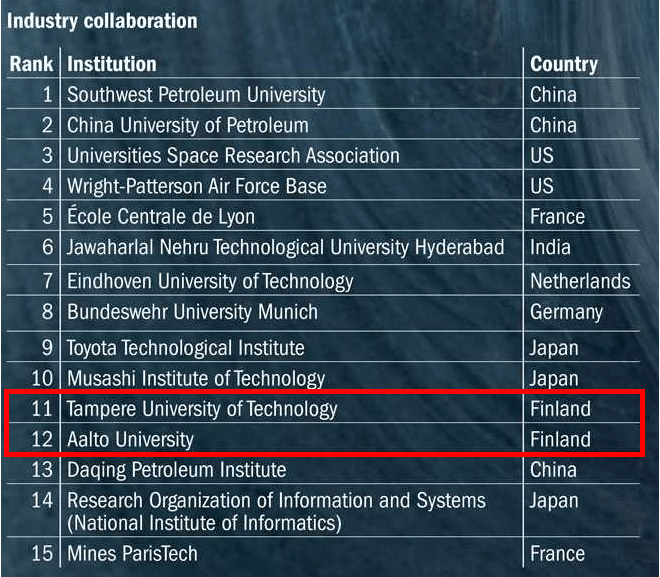

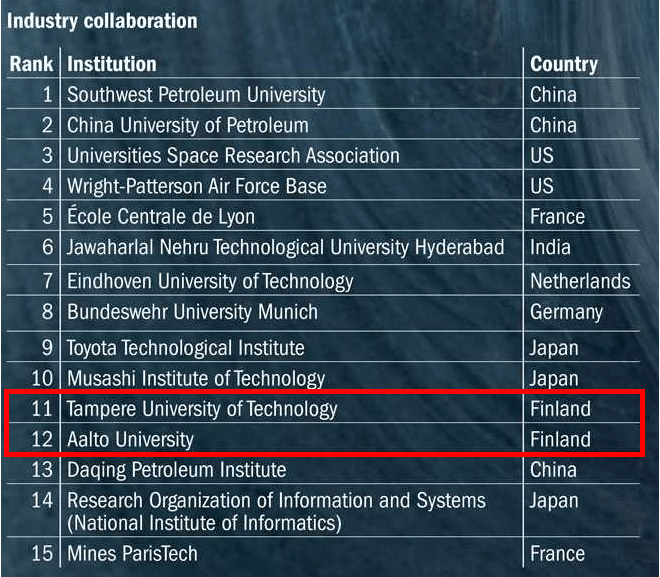

According to Kulmala (2016) a key factor to the success it that innovations are to be developed on a “generic level”, so that all encompassing parties can make use of the newly generated knowledge in their own way. In addition, the Finnish mentality and culture is very well suited for open innovation paradigms and concepts. This statement refers to the fact that a flat hierarchal structure in a norm in Finland and that the people are very honest, frank, and open about even confidential matters. This occurrence is very well illustrated by a quotation from a Finnish industry leader Stig Gustafsson: “Finland is not a country, it is a club”. Essentially this means that the dynamic and behaviour in Finland business and industry environment is similar to a community of some sorts. Evidence supporting this statement appears in industry collaboration rankings (Table 2), where one can clearly see that two of Finland’s top technological institutes reach high ranks. Therefore, it appears that open innovation paradigms in Finland have enormous embedded potential. Additionally, one must notice that the Finnish universities are not bound or obliged to specific industry, such as the petroleum industry. Thus, if these “married” universities were excluded, then the Finnish institutes would peak the rankings.

Table 1. Results of companies participating in fimecc’s open innovation programmes compared to random technology companies who do not participate

Table 1. Results of companies participating in fimecc’s open innovation programmes compared to random technology companies who do not participate

Table 2. Industry collaboration rakings. The ranking provides an idea of how much companies are involved in and invest time in the active research of the institution (Times Higher Education, 2016)

All in all, it is obvious that traditional, closed, and internal R&D practices will increasingly become more of a challenge for companies in the future. Cost is the major issue, but also the speed, time-to-market, of which new ideas and innovations are introduced will be a more crucial factor for the survival of firms. There are many observed alternative solutions for companies to enrich themselves through an outside-in flow of ideas and innovations, however, these solutions are only partly aligned with the open innovation concept. It is clear that under the right circumstances, true open innovation paradigms are not an utopia and hypocrisy. Instead the concept can be extremely useful and valuable source of new ideas, as it was observed with Dimecc. Hence, open business model logics have huge unknown potential that needs to be further exploited.

/Drill

References:

Bergmark, H,, 2015. Interview. April 16th. 11:30

Chesbrough, H.W., 2006a. Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business Press.

Chesbrough, H. ,2006b. Open Business Models: How to Thrive in the New Innovation Landscape. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Chesbrough, H. (2010). Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers. Long Range Planning, 43(2-3), 354-363.

Chesbrough, H., 2012. Open innovation: Where we’ve been and where we’re going.Research-Technology Management, 55(4), pp.20-27.

Chesbrough, H., 2013. Open business models: How to thrive in the new innovation landscape. Harvard Business Press.

Chesbrough, H. and Brunswicker, S., 2014. A fad or a phenomenon?. The adoption of open innovation practices in large firms. Research-Technology

Management, 57(2), pp.16-25.

Cisco, 2016. What is the Cisco I-Prize?. [Online] Available from: https://www.cisco.com/web/solutions/iprize/info.html#ov1%5BAccessed 19 August 2016].

imaa, 2016. M&A Statistics. [Online] Available from: https://imaa-institute.org/statis tics-mergers-acquisitions/ [Accessed 14 August 2016].

Innocentive, 2016. About Us. [Online] Available from:

https://www.innocentive.com/about-us/ [Accessed 14 August 2016].

Kallonen, A., 2016. Interviewed on 4th May. 09:00.

Keeley, L., Walters, H., Pikkel, R. and Quinn, B., 2013. Ten types of innovation: The discipline of building breakthroughs. John Wiley & Sons.

Komssi, M., Pichlis, D., Raatikainen, M., Kindström, K. and Järvinen, J., 2015. What are hackathons for?. IEEE Software, 32(5), pp.60-67.

Kulmala, H., 2016. Interviewed on August 9th. 13:30

Times Higher Education, 2016. Alliances in Science: Innovation Indicators.

Productivity Commission, 2016. Digital Disruption: What do governments need to do?. Australian Government Productivity Commission Research Paper. June 2016. [Online] Available from:http://www.pc.gov.au/research/com pleted/digital-disruption/digital-disruption-research-paper.pdf

[Accessed 14 August 2016].

Wert, J., 2016. Interviewed on 15th September. 09:25

World Economic Forum, 2015. Industrial Internet of Things: Unleashing the Potential of Connected Products and Services.

Table 1. Results of companies participating in fimecc’s open innovation programmes compared to random technology companies who do not participate

Table 1. Results of companies participating in fimecc’s open innovation programmes compared to random technology companies who do not participate